We’ve all heard it before. Translators are here to stay, machine translations are still premature, CAT tools can’t really make a dent. It’s been like a mantra every single year since I began translating in 2006.

But this year it’s been quite different. 2013, and we’ve already seen a 50M+ inflow of investments into the language industry, from Duolingo (translation services provided by language learners paying for their language education) to Gengo (crowd-sourcing). There are 86 new startups, 770 investors, doing things from crowd-sourced instant visual/audio translations on the go (Waygo) to software localization platforms like Phrase.

More mature companies like LionBridge and SDL are actively investing in language technology and crowd-sourcing. TAUS has written extensively on this in the beginning of this year (Choose your own translation future). The main questions were:

1. Will machine translation take a big role in the translation industry or not?

2. Do we have to fear that translation will become a free-for-all service?

3. Will the closed (competitive) or the open (collaborative) business models prevail?

Similarly, Common Sense Advisory wrote last year:

“We see a phenomenon in translation as it shifts from a cottage industry to a much more technology-dependent one, with large volumes of content flowing in many directions.”

Beginning of this year, the Economist wrote about how tremendous technology has advanced in terms of simultaneous translations by using crowd-sourced data. Blogger Federico Pascual has also written to dispel the age-old myths on the quality or performance of machine translations. His conclusion?

“By now, it should be clear that Machine Translation (1) is in use today and (2) is part of the process that provides corporate users with good or “good enough” quality, a process which also includes (3) human translators, who are and will always be an essential piece of the localization puzzle.”

One common advice all of these reports have indicated is the need for translators to become specialists. Translations that require specialized expertise (such as academic publishing) will always need translators who are trained in the domain. Specialization means formal academic training or work experience in a highly specific field.

But I think what none of these articles do really, is explain how exactly the industry is changing in the front lines of software development.

As a startup co-founder, I think I can provide some insight as to how young and mature businesses and investors are looking at the industry. And the results are not optimistic, being first and foremost a translator.

I want to use Conyac.cc as an example for this “new disruption” mentality that we’ve seen over the past five years.

CONYAC’S BUSINESS MODEL

Conyac is a real-time outsourcing platform. End-clients submit translation requests, and the translation request is broken into different segments, or “strings”, which translators ‘all over the world’ work on.

Depending on the size of the project, one project can include 10-15 translators, and a number of reviewers. Conyac has paid around a total of 159,194 USD to translators worldwide since launching in 2009 (around 3 years of operation). They currently have 10,000 users, and they’ve raised around $500,000 in funding from a handful of Venture Capital firms. Conyac has 20 employees in Tokyo and San Francisco, and plan to open offices in Singapore and Luxembourg.

TechCrunch quotes they generate “$50,000 in revenue” in each month, if that’s the case, why a total payout of only $159,194 USD over 3-4 years of operation?

Points System

All translation requests are translated two times. The first two translators are awarded “points”. One USD = 100 points, and the number of points awarded to the translator varies with a predetermined ‘points schedule’ which Conyac does not provide (Conyac provides only the end-client points-schedule). Once the translation request is translated at least two times, it’s sent into the Review process. The reviewers review the translation and the highest rated translation is delivered to the client.

Once users rack up enough points for each cash-out levels (500 ($5), 1000 ($10), 5000 ($50), 10,000($100) points), Conyac pays out via PayPal, charging also a cash-out transaction fee. Points are expired within six months if the translator does not log back in.

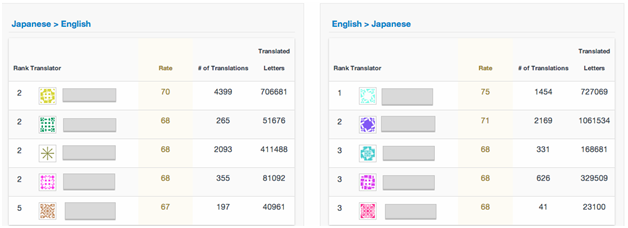

Translator Ratings

Each translator has a “Rate” or a Rating. All translators begin with a rank of “50” and move through the ranks:

Starter translators can provide translation work but cannot cash out. Once the Starter receives enough reviews from “Standard” translators or earns a rating of 53 or more, the Starter is promoted to a Standard Translator.

Standard translators gain access to “premium” or “business” requests, or so-called “professional” quality translations only after they have reviewed at least three translation works.

Trainee – the Translator is demoted to Trainee when he has failed to meet the Starter criteria and must demonstrate his skills through reviewing other’s work or performing translations

The objective here is to create a system where translators review each other with the incentive that they would be promoted to standard translators or would be able to access requests for higher paying jobs.

Pricing

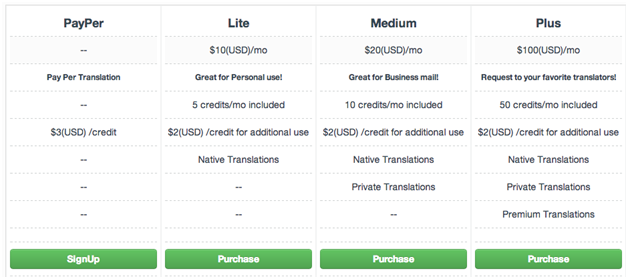

To end-clients, Conyac offers pay per project, and three monthly plans: Lite/Basic, Medium/Plus, Premium, which cost respectively, $10/mo, $20/mo, $100/mo. Correction: They’ve recently changed it exponentially to $250/mo, $600/mo, $1000/mo (See here).

As if this wasn’t convoluted enough, there are three levels of translations, which is part of the package.

Native Translations: Translations performed by Starter Translators, I assume. As opposed to what? Non-native translations?

Private Translations: “Your translation requests will only appear publicly on Conyac for 24 hours. Protected from search engine crawlers.” –I have no idea what this means, are translations crawled by Google and other Search Engines?), and

Premium Translations: “You can select from our most highly rated translators and make a request directly to your favorite translators.”

Each package is expressed in points, 20,000 pts for Basic, 60,000 pts for Medium, and 110,000 pts for Premium. Again, 1 USD = 100 pts.

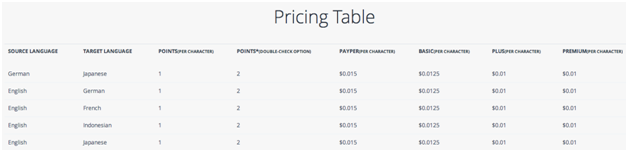

Here’s the Pricing Table. On the left four columns they are expressed in points, on the right three columns you’ll see the actual costs expressed in USD.

For example, for Japanese to English, Conyac charges 4 points per letter or $0.05/source letter/character. We’re talking about source letter or character, not target words. Naturally, I don’t think the client really cares about what goes on behind Conyac or why they would have such a convoluted system.

They just know it sounds cheap, and they’re going to get multiple eyes looking over the same text over and over again at no service charge.

CONCLUSIONS

In the end it’s still unclear how much Conyac pays each translator, since the translator’s points schedule is not disclosed. It’s obviously not the case that two translators will be compensated for the same work at the end-client points schedule. But we can say very fairly, based on the total payout, the translator does not even make $10,000 a year.

But Conyac is not the only one. Look at MyTranslation with “Auction Translations”, or yet another RFP/Job bidding system, look also at another start-up Tran.sl, who has a “council” that punishes “unreliable translators and prevent them from working with us again”, that has a real time bidding platform (“Think real-time ebay on steroids”—no joke, I’m really quoting this).

All these new businesses, sustainable or not, are based on how to game the crowd-source movement. They represent not singular mentalities or approaches, but the larger view of where the localization industry is going, especially for companies like Lionbridge and SDL, who grow largely by mergers and acquisitions.

The industry is changing, but all you see is freelance translators gradually losing ground and an industry quickly deteriorating before the end-client has even had a chance to understand how the industry has worked traditionally.

What was once an invisible group of labourers has now become demoted to low value services like virtual assistance, data input, survey completion, or what Conyac would call “trainee” services.

I think 2013 is a year when we really begin to have a more serious conversation as a community of software developers, translators, and agencies, where the industry is heading towards.

If we believe as translators, we’re here to stay, it’s time to get together and make a difference.

Author bio

Anthony Lee is a JP/CH-ENG medical translator who has been translating since 2005. Anthony recently co-founded TransBunko, a specialist translator network, and blogs about the industry at the TransBunko Blog. Follow him on Twitter @transbunko.

“Think real-time ebay on steroids” – Oh, my! I don’t know whether to laugh (you have to admit, it’s quite funny) or to cry over this issue of crowd-sourced translations. Thank you for such a detailed post, Anthony. It has really given me (and all of us) a better idea of how these platforms work. When I find the time, I will also write a post on my experience with them (in terms of quality, customer service and also cost).

Customers, like you said, don’t really know what the translation process entails, but it is our duty as professionals (translators, agencies – old model, not this new type of crowd-sourcing sharks) to educate them. I try to do this every time someone complains our prices are too high and they found an agency charging £0.02/word (!!!!) – it happened recently.

Hey Alina, thank you for the kind words 🙂 Exactly, what I wanted to show was the really imperious treatment on part of these new companies and how this is resulting in a diminished recognition of the trade.

Especially in software development, where localization of several Linux-based OSs have been volunteered by developers worldwide. When I speak to people outside of the translation industry, they always speak of translation as “converting”. Overtime, the public has been gradually taught to see translation as a mechanical process.

Anthony

I had read about these word-mills and was impressed with the administrative side of their operation.

The reality is that there is more work being generated than there are professionals to take care of it. So, people will use what ever is available and savvy entrepreneurs will grab the momentum and run with it.

The need is real. The shortage of professionals is real. The lack of knowledge of what our work entails is real. Ready-made solutions are popping up every where and people are taking advantage of them.

Reality bites. In this case, everyone will get bitten, except, it seems, the middlemen – that is, if their contracts have a very well written liability restrictions clause.

Very well written, Anthony, thnak you. And thank you, Catherine for making this available to us.

Hey Giovanna,

“Ready-made solutions are popping up every where and people are taking advantage of them.” That’s exactly it. As a software developer, I believe in the power of technology to do good and reinforce positive behaviour and standard operating procedures.

But because software localization has an equally low barrier of entry (it’s so much easier to develop with open-source frameworks now compared to what it was 10 years ago), what you see is a flock of people trying to capitalize off the same game played by the pioneers of crowd-sourced translations. And it’s very easy to be completely disconnected or misguided in the process.

Anthony

I’ve already burst this bubble. For a good laugh and a look at the abysmal results of crowdsourced translations, please read http://www.loekalization.com/crowdsourcing.html

Loek, your article approaches it from a different perspective. I have read a handful of articles on crowdsourcing and most of them have added to my understanding of the process in its broad sense and various perspectives: vendors, buyers, participants, end-users of the “translated” products, impact on our industry, impact on the perception of our profession as such, etc.

There is need for this type of service due to the massive influx of data, but better quality control is definitely needed. The answer? We are not there yet.

@Loek, Great, thanks for the read. I think it’s important that everyone has a say and contributes to this.

@Giovanna, multiple narratives from multiple stakeholders–that’s the key!

Excellent post, Anthony. I’ve been reading though Jaron Lanier’s “Who Owns the Future” again, which talks about how top servers use big data to concentrate wealth. Much of the inequality that now characterizes the economy stems from just this mechanism. What you so beautifully describe going on at Conyac — excellent earnings, miniscule payouts — goes on throughout the economy. The entire financial services industry is based on the big server/data model. Not to mention excellent earnings and miniscule payouts. And of course, the whole TAUS “translation automation / translation as a utility” model will inevitably do the same.

I keep asking myself whether there isn’t another way of structuring the technology such that this outcome is not inevitable. I don’t see it. But as someone involved with technology, what do you think?

Best,

Ken

Hey Kenneth,

Thanks for commenting. I think the first thing is to make sure we mean the same thing when we talk about big data : a data-driven approach to consumer behaviour and product development. In the field of translation automation and machine learning, one “big data” approach is to collect as much information on different linguistic corpora by actual users. The goal is to segment source texts and allow users worldwide to generate target texts. Once you’ve collected enough source-target data you can improve methods in statistical relational learning, inductive logic programming, and explanation-based learning–all of which help build and enhance natural language processing systems.

I don’t think Conyac is collecting that information at the moment. But it would be one of the more valuable assets they could collect. It takes a tremendous amount of time to do so. Google has been doing this for years because of access to websites and books published worldwide. Google’s Translator’s Toolkit also collects user generated data and translations. In any case, we’re still a few years behind creating a viable, functional natural language processing system.

I’m no Luddite when it comes to this–I find this fascinating. However, what I did want to explore through this article was the pervasiveness of this top-down type of attitude which demotes and undermines the status of translations and translators, especially to end-clients. I’ve had too many people come to me and think that translation is “conversion” like a foreign exchange conversion. It’s bad enough that translation is the 3% in the publishing industry , I don’t want end-clients to believe that translation is something that any bilingual person can do. Especially when the material involves domain expertise.

I do believe in technology and innovative business models–I think we’re able to reinforce positive behaviours and introduce new models to sustain and promote new jobs. The key is finding a model that encourages transparency of the translator, end-client understanding of the industry, and fair rates, –it’s about creating a compelling story that humanizes translators, especially specialist translators. I think it’s possible and that’s what we’re trying to do now.

Sorry for the long response!

Anthony

Hi !

Thank you very much for your great article ! It is good to see someone who really cares about the heart of that system : the translators.

We see out there some crowd translation platform which speaks about “human translation machine” and “from developper to developper”, with no consideration for the translators, often unpaid (and I don’t speak about free open source project).

The translator side is often forget, with no gamification or real awards for the hard work.

My question is : Does a good, ethical translation platform which pays right its member exists ?

I mean, why would a regular person become a translator if it work seem to has “no value” ? Why would I, as a translator, work for such platform, if I’m only considered as a “human machine” ?

“If code is poetry, translation is art.”